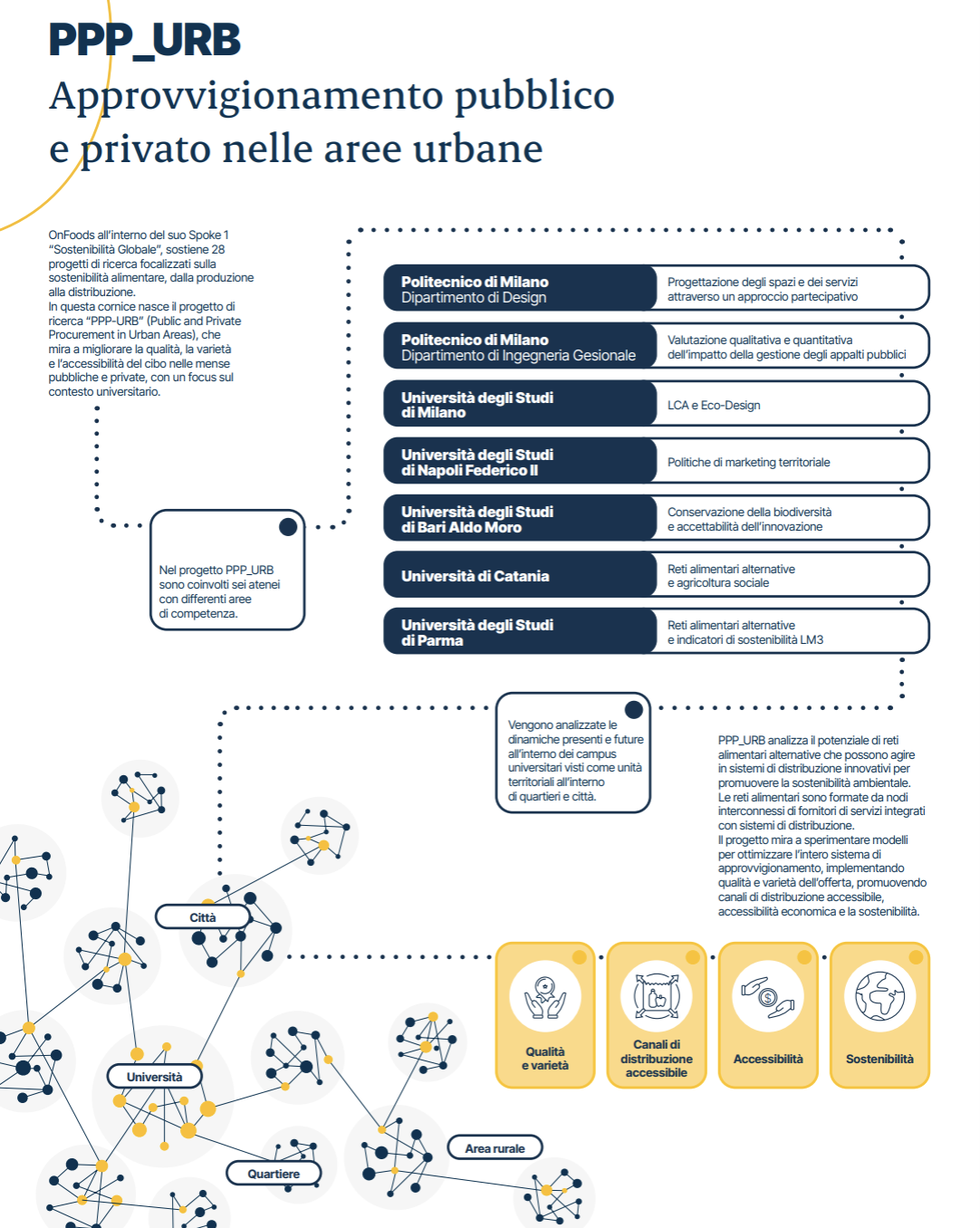

Funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3, Theme 10.

Public food procurement has the potential to radically transform the food system, influencing what thousands of people consume daily in canteens and public spaces.

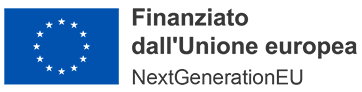

In this thematic context, the Politecnico di Milano coordinates the research project “Public and private food procurement and short food value chains in urban areas” (PPP-URB), which aims to explore and implement innovative policies in the public food supply sector, with a particular focus on universities.

University campuses are complex and dynamic environments that can be considered as urban microcosms. Considering universities as territorial entities similar to neighbourhoods and cities allows analysing their evolution and potential integration with the surrounding urban context. From here, research can develop scalable and replicable models for food supply in universities.

We discussed this with Professor Davide Fassi, from the Department of Design, who coordinates the PPP-URB research project.

✅ Professor Fassi, we know that “Public Food Procurement” is the process of sourcing food that determines what thousands of people eat every day within canteens and public spaces. For this reason, its management holds enormous transformative potential and significant responsibilities for the entire food system. After decades of limited interaction between the State and the market, the idea that governments can and should use public administration to pursue social, environmental, and economic goals is beginning to gain ground once again. Is this trend also occurring in the context of public food supplies?

The project I'm leading within OnFoods is centered on the food procurement policies of a specific public institution: universities.

From the outset, it was evident that we wanted to investigate public canteens. As the project took shape, we further honed in on university dining services, which, for a number of reasons, provide an ideal model for our research.

In Europe, there are currently no significant mandatory regulations regarding food supply and distribution. The EU only has the “Green Public Procurement” (GPP) as a tool to promote the acquisition of environmentally sensitive food products and services, making them more strategic and sustainable. These guidelines are voluntary and provide recommendations to European public authorities, primarily aimed at purchasing eco-friendly products. Consequently, the public food procurement sector has yet to be regulated, unlike other sectors related to the ecological transition.

There is a clear need for more binding regulations on the social, environmental, and economic sustainability of public food supplies. However, these regulations should not only focus on system efficiency but also on integrating short food value chains, emphasizing the local dimension. They should also pay close attention to system circularity, which, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, is the “ability to be regenerative by design,” meaning based on the design of products and processes.

There is a clear need for more binding regulations on the social, environmental, and economic sustainability of public food supplies. However, these regulations should not only focus on system efficiency but also on integrating short food value chains, emphasizing the local dimension.

✅ The lack of a clear regulatory framework is both a problem and an opportunity, as it leaves room for maneuvering and proposing scientific research. Is that correct?

When there are no mandatory regulations, the system moves towards experiments implemented according to the will of individual institutions.

In the mid-2000s, for example, eco-labeling of products was not fully regulated, and ISO criteria were yet to come. Everyone acted on their own initiative, resulting in a patchwork of product labels and initiatives from individual companies or consortia.

This is what is happening today in the food procurement sector: numerous initiatives, but no real systematization. However, it is precisely in this gap that scientific research can step in, driving studies that, hopefully, may positively influence future policies.

To achieve this, we must start with a mapping of best practices: in-depth analyses of the most virtuous situations. These need to be systematized, proposing improved implementations that could eventually inform a legislative process that, one day, is expected to become mandatory.

Our research group decided to focus the investigation on universities. Although not a closed system, universities have strong connections with the city, the neighborhood, and the local agri-food production network. In many ways, a university functions as a city within a city.

We are working with a type of public administration that, on a different scale, shares strong similarities with more complex organizational structures. We believe that this model could generate other models, potentially scalable to different levels.

Although not a closed system, universities have strong connections with the city, the neighborhood, and the local agri-food production network. In many ways, a university functions as a city within a city.

✅ A designer, moreover, has more opportunities for experimentation whenever there is a gray area…

At the core of research in the field of design is precisely this: projecting onto scenarios and creating visions of possible or probable futures.

The designer engages in traditional research activities to perform backcasting and forecasting. Using the tools and processes of lateral thinking, systemic design, or trend reception, we design futures based on data and projections.

It is clear, then, that as you mentioned, the gray area is also fertile ground for imagining disruptive solutions, as it offers more freedom from constraints.

✅ The disciplines of design have been oriented towards user-centered approaches for decades. More recently, participatory design methodologies have become widely adopted. How do these so-called participatory practices or methodologies apply to food systems?

These methods are highly flexible and applicable to numerous subdomains. The general approach involves bringing together various stakeholders of the food system —producers, distributors, consumers, intermediaries. In the case of our research in universities, we engaged students, faculty, and administrative staff to collaborate on solutions to well-defined problems.

Collaboration entails not only using methods like interviews or quantitative surveys but also employing approaches that bring out people's design capabilities. Design skills are then used to transform these ideas into potential solutions.

As you mentioned, design has long evolved beyond mere product creation, increasingly shifting towards designing services or "products as services." In this transition, the discipline has expanded its toolkit, moving away from predominantly hardware to more software-oriented tools such as participatory design, co-design, fieldwork, rapid prototyping, and testing, all of which have become crucial methods. These methods, applied in the short term, can provide valuable insights for implementing a service in the medium and long term.

For example, when considering the distribution of a "farmers' box" within a university, it's essential to identify and test each step of the experience, the "journey." Evaluating and validating each step helps make the service more efficient.

Collaboration entails not only using methods like interviews or quantitative surveys but also employing approaches that bring out people's design capabilities. Design skills are then used to transform these ideas into potential solutions.

✅ Opening the design process from the outset to all stakeholders can lead to radical changes compared to the researcher's initial vision: how does a designer adapt to the continuous change that participatory practices imply?

It's a fundamental issue, and in my opinion, it lies at the heart of participatory design processes. In fact, it is desirable that by involving different types of people, non-canonical ideas emerge "out of the blue," unexpectedly diverging from the originally envisioned solution. These ideas can offer a fresh perspective, charting alternative paths that, while not necessarily leading to the initial solution, provide a different and enriching viewpoint.

It's a complex process because adding components to a system increases its management complexity. However, by involving those who will use or implement the solutions, regardless of their role, a higher degree of acceptance of the solution itself is ensured, because it has been generated through an inclusive process.

A concrete example: 12 years ago, we created a community garden on our university campus ("Coltivando"). At the time, it was an innovative idea, considering that Politecnico di Milano does not offer degree programs related to agriculture or biology. We embarked on a process of listening to the community, followed by participatory design involving approximately one hundred people. After collaboratively finding the solution for the garden in terms of spatial layout, materials, and operation, we dedicated every Saturday for a year to its implementation, involving nearly 2000 people on an area of 800 square meters.

This process has allowed many people to feel part of the project, and the benefits have been evident over the years. For example, there have been no acts of vandalism, and the garden remains recognizable and vibrant in the neighborhood. This openness of the project has also encouraged school visits and activities with stakeholders, ensuring the project's sustainability over time.

After 12 years, the garden is still there, cared for by a group of volunteers who, although changing over time, are evidence that the place has a history of participation that keeps it alive in the present.

In the context of urban agriculture, there are several examples of community gardens that do not endure over time because often the implementation process did not prioritize people. Our example demonstrates that genuine and participatory involvement can make a difference in the longevity and success of a project.

✅ You coordinate the research project 'Public and private food procurement and short food values chains in urban areas' (PPP-URB). Let's delve into the specifics of the project…

In the initial project meetings, we encountered a significant diversity of contributions among the partners. This diversity has opened up interesting but complex scenarios to manage, requiring an orchestration approach akin to that of a designer.

We engaged with seven different disciplines, ranging from agricultural law to management engineering, design, agronomy, and other scientific fields with markedly different approaches. Initially, we sought to identify each university's areas of expertise and understand how they could contribute to the project theme.

Before proceeding, we analyzed a series of best practices related to our respective areas of expertise. This was helpful in familiarizing the group with a common language and creating a cohesive team, comprising approximately thirty individuals. The goal was to avoid parallel work and instead create points of contact to achieve a common objective.

It was indeed quite challenging due to the complexity of the group and the various disciplines involved.

The initial mapping of expertise areas allowed us to understand that this diversity within the system was actually an asset, as it enabled us to approach the food procurement theme from multiple perspectives. The challenge lay in determining how this observation could translate into practical implementation and concrete project outcomes.

PPP-URB consists of three main phases: the first, lasting one year, involved a survey of best practices related to public food procurement; the second phase identifies action strategies; and the third phase focuses on experimentation. PPP-URB is a research project with a strong experimental component that aligns well with scenario building methods and the development of unconventional solutions.

We aim to provide inputs that can help go beyond existing regulatory constraints because experimental research also operates outside the current context, aiming to - like saying - 'hack' it.

✅ Explain how you divided the work among the various partners and how you are coordinating.

The project partners include six universities, covering seven areas of expertise, as Politecnico di Milano contributes in two fields: design and management engineering.

Politecnico di Milano is responsible for designing spaces and services using a participative approach. Additionally, with expertise in management engineering, they conduct quantitative and qualitative analyses of the impacts related to the management of public food procurement.

University of Parma, on the other hand, is highly focused on alternative food networks and sustainability indicators. The university is actively involved in the development of agricultural bioregions in the Parma area.

University of Bari brings a diverse contribution, involving four different disciplinary scientific sectors and addressing themes such as biodiversity preservation and territorial innovation. They also have a strong connection to the short food supply chain and collaborate with agricultural companies committed to biodiversity preservation.

University of Milan focuses on life cycle analysis and ecodesign, seeking to understand the environmental impact of various stages of food production and packaging through Life Cycle Analysis.

University of Catania, on the other hand, is dedicated to social farming practices, engaging in social agriculture activities in their region and showcasing local best practices related to rehabilitation through agriculture, including projects involving prisons.

Lastly, University of Naples (Unina) specializes in territorial marketing policies, studying marketing strategies for local production to promote distribution and consumption.

✅ The project investigates the dynamics of procurement and consumption within university campuses, viewing these spaces as urban microcosms. We perceive universities as territorial entities akin to neighborhoods and cities, analyzing how they evolve and integrate with the surrounding urban fabric. How has your work progressed so far in these unique "food environments"?

Often universities are perceived as separate entities, akin to alien bodies landing in a territory, yet remaining detached from it. The project's intention is to overcome this perception, recognizing public universities as spaces with specific and unique rules, but nonetheless public spaces.

Thinking of universities as permeable rather than closed environments is crucial for fostering connections on various issues, including food.

The theme of universities and campuses operates on three scales: the neighborhood, the city, and the peri-urban fabric. At the neighborhood level, we considered the impact on the local economy of food establishments such as restaurants, delicatessens, and neighborhood shops. All of these could engage in dialogue with food distribution and consumption within the university, benefiting from the presence of students, faculty, and administrative staff.

On the city scale, we explored connections between different production and distribution systems. For example, in Milan, there are wholesale fruit and vegetable markets that supply local markets, some of which are close to university campuses. We considered how these entities could potentially become suppliers for the university.

Lastly, we examined the peri-urban fabric, such as the South Agricultural Park of Milan, abundant in short food supply production. Our goal is to understand how these entities can engage in dialogue with food procurement within the university.

Considering that the university community can reach numbers comparable to those of an average city—such as Politecnico di Milano with its 45,000 students and 8,000 staff and faculty at the Bovisa campus—the impact can be truly significant.

✅ Have you identified similar best practices outside of Italy?

We are currently conducting this survey, which extends beyond the mapping of expertise areas we completed in the first year. We are looking at similar practices in universities worldwide, leveraging international rankings and personal network contacts.

What emerges is a highly diverse landscape, as some universities have sustainability programs that tangentially include food. For instance, there are food programs catering to vegans and vegetarians, community gardens providing food, and educational seminars promoting awareness of plant-based diets.

Others have specifically focused on food within the campus, treating it as a complex system of practices.

Harvard University in the United States has been engaged in urban agriculture experiments for over a decade, integrating both teaching and research with strong community involvement.

In Italy, Bocconi University has developed a well-established food policy inspired by best practices initiated during Expo 2015, and by concrete food policy instruments adopted by metropolitan cities such as Milan and Turin.

By the end of this year, with PPP-URB, we will be drafting food policy guidelines for universities. Following this document, each project partner will seek to implement some of its components within their respective contexts.

For instance, the University of Parma will collaborate with the newly established Parmense bio-district to make it a supplier for the university cafeterias during an experimental period of at least 3 to 6 months.

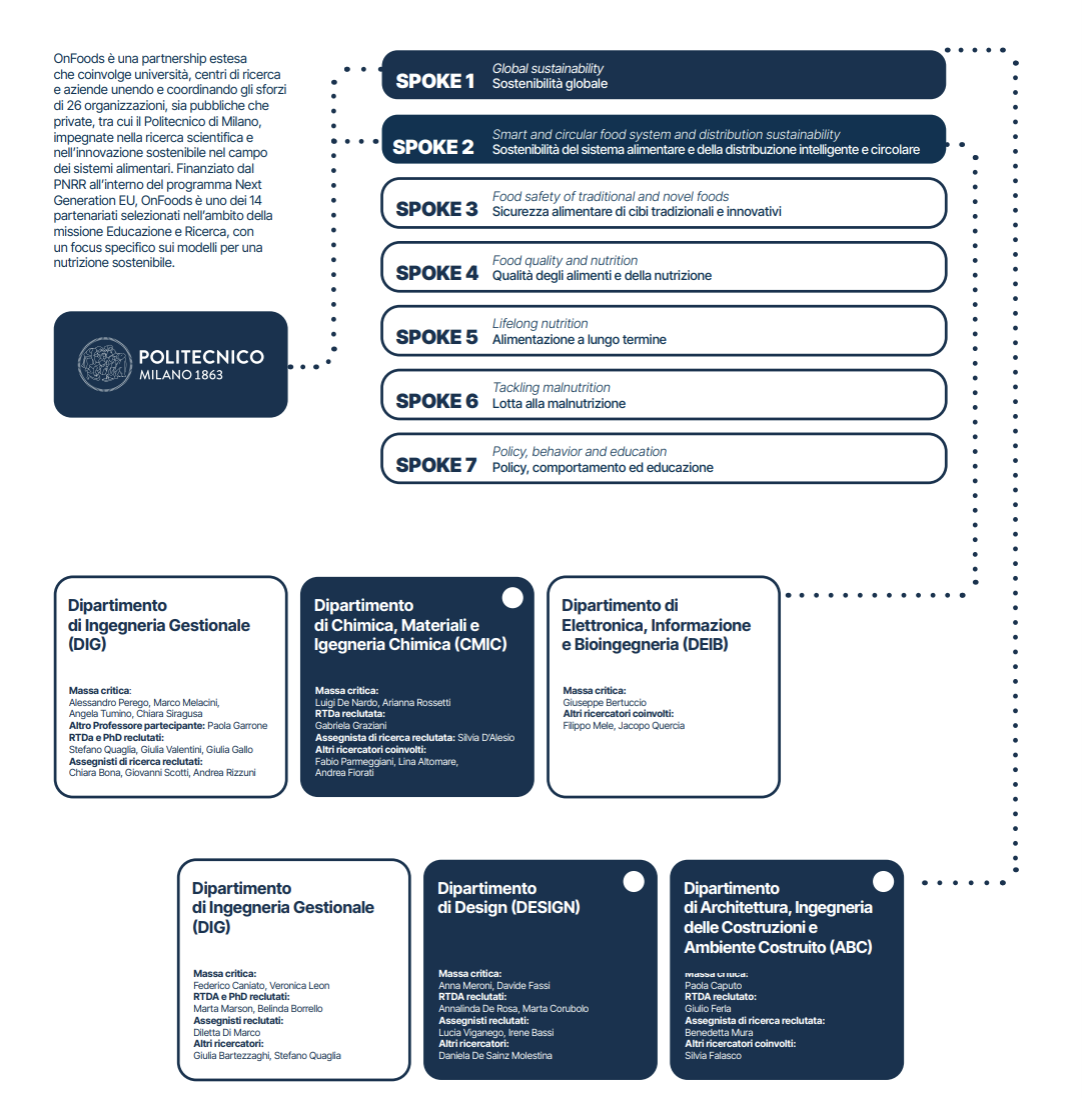

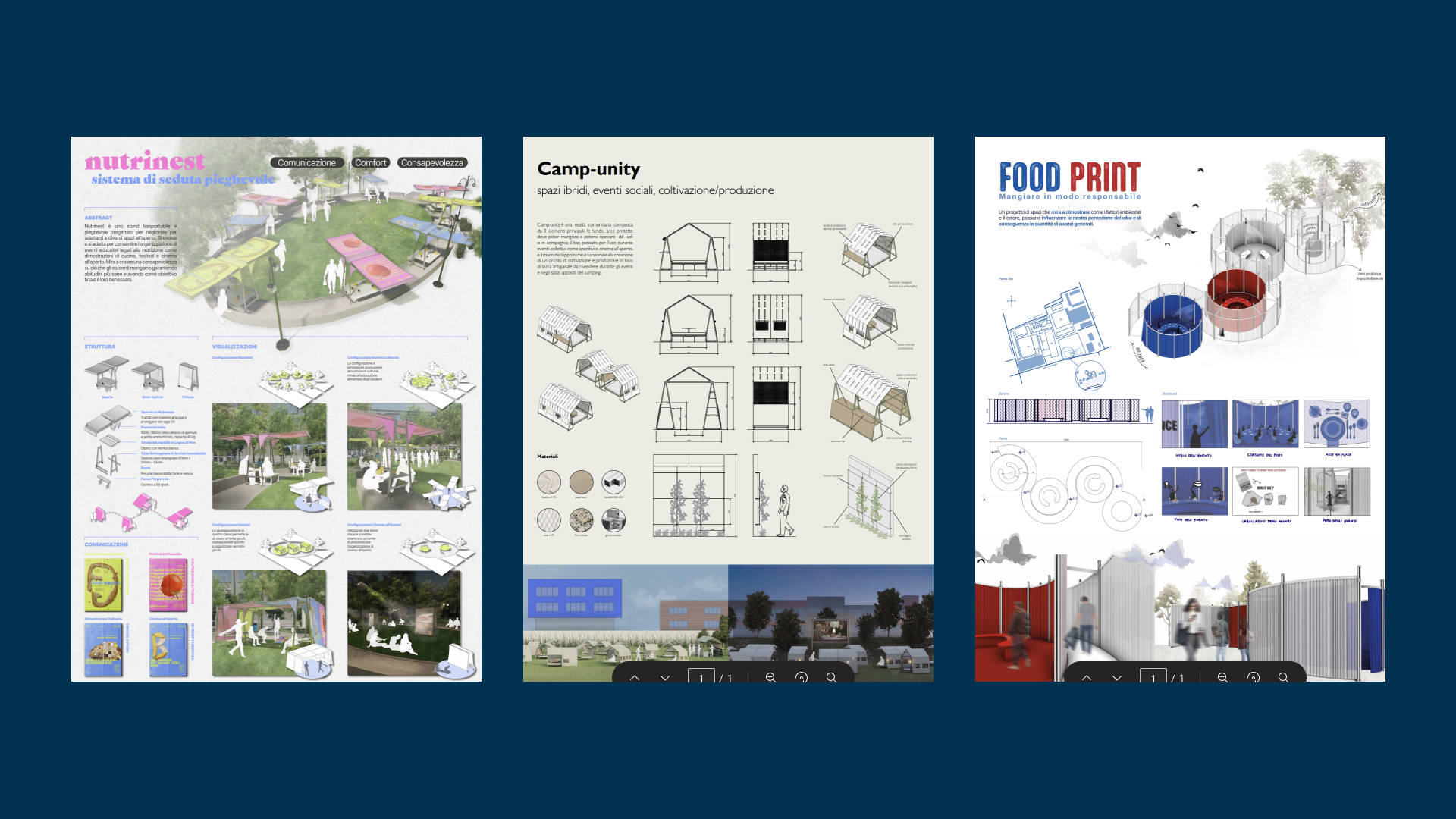

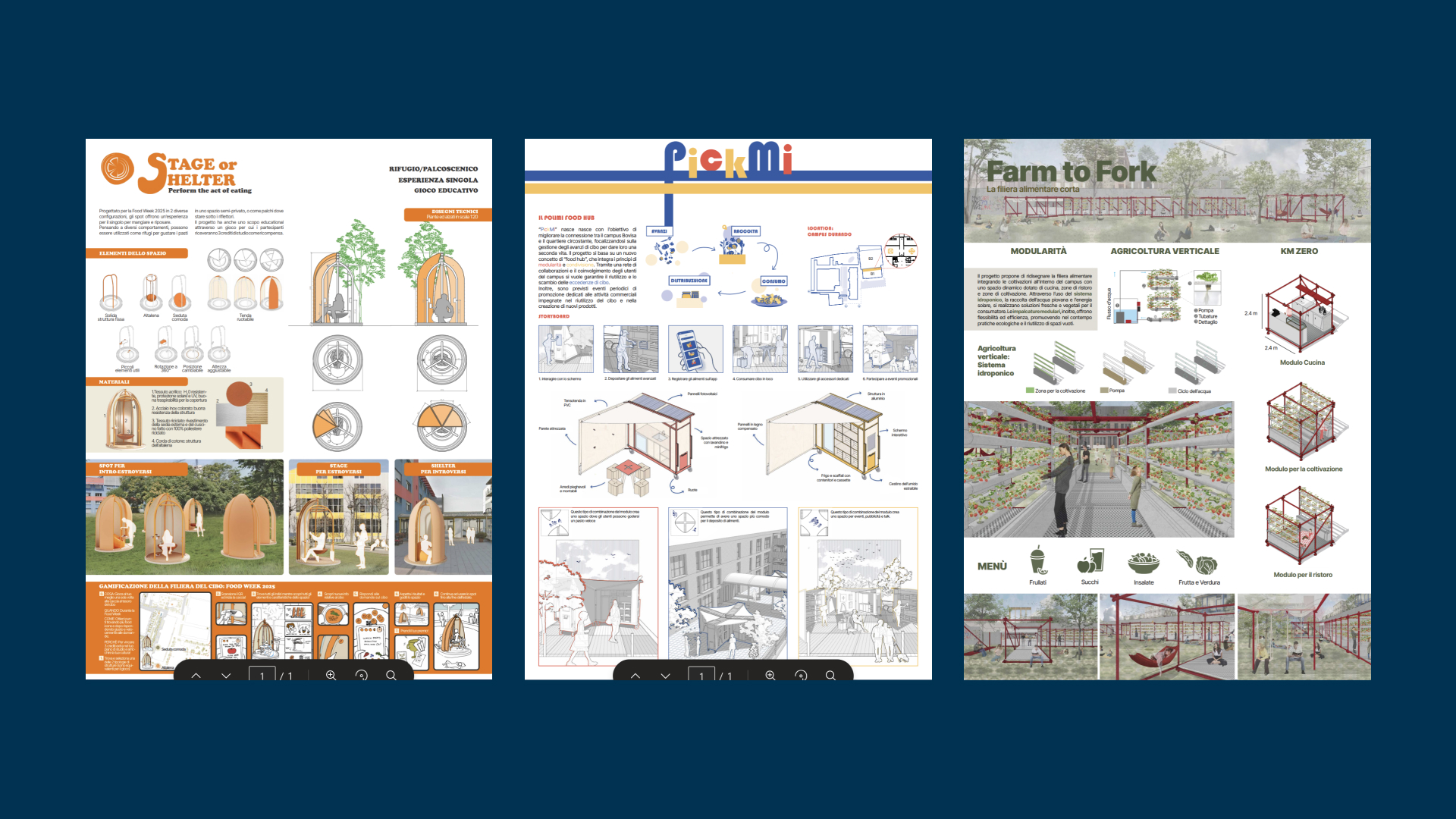

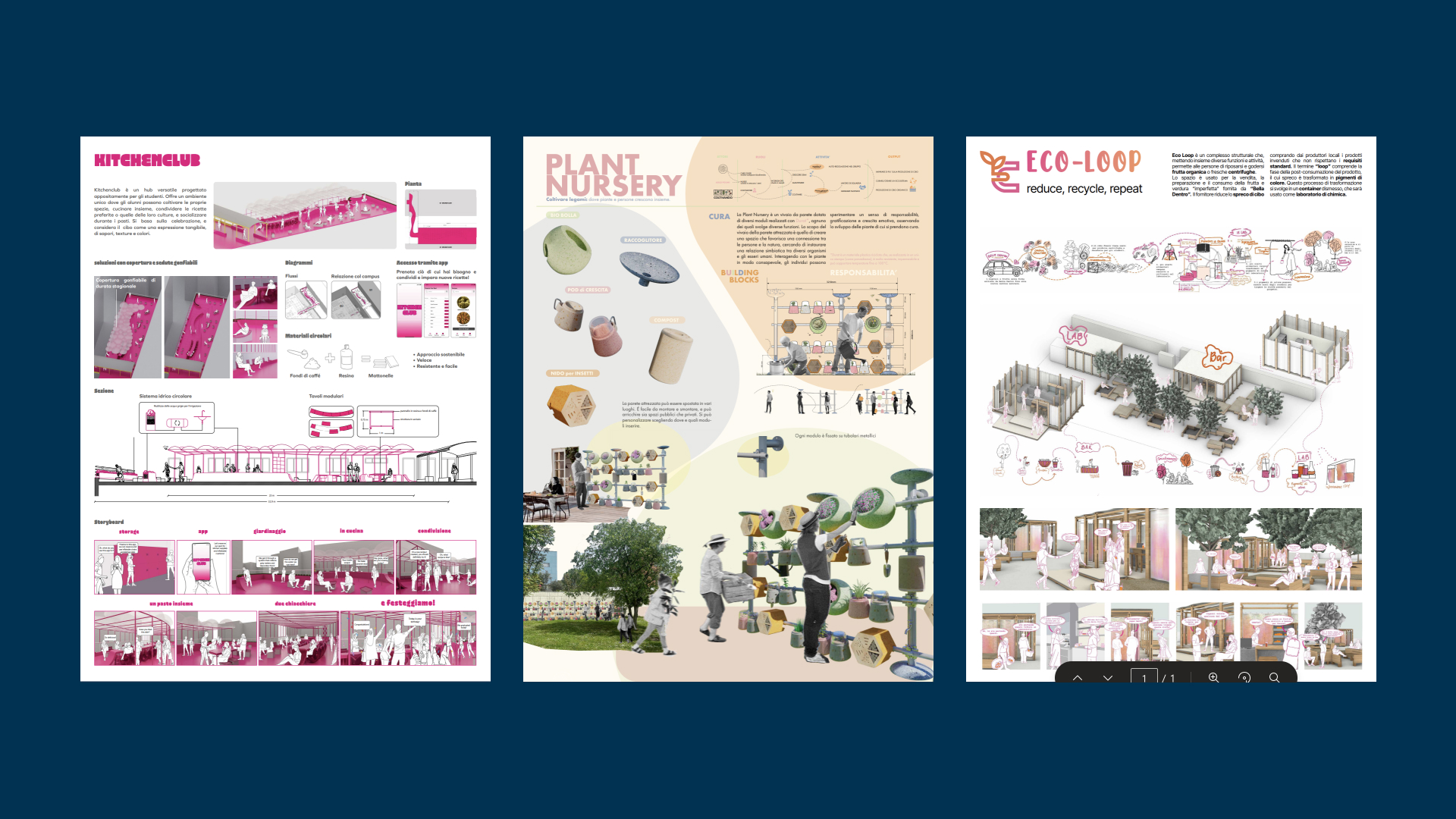

✅ Recently, Politecnico di Milano participated in the Food&Science Festival in Mantua with a booth showcasing various projects, including the work done together with master's students within the framework of PPP-URB. In an initiative called "Tasty Spaces," students and researchers from Politecnico's Design department engaged the public with several projects aimed at reimagining our relationship with food within educational and academic contexts. We attended 10 experimental projects that envision and prototype innovative solutions for socializing common spaces, food preservation, and even the production of fruits and vegetables within university campuses.

We often involve students from Master's degree programs: it's a working method we frequently use in research projects because it allows us to assign real design themes to students, exploring alternative ideas and understanding how they can be integrated into possible field solutions.

At the festival, we aimed to present projects that encourage interaction with a broad audience, rather than focusing on advanced aspects of the research project.

It was also an excellent exercise in developing soft skills for students and young researchers: communicating with people and explaining one's work clearly and engagingly is by no means straightforward.

This blog post is related to

Global Sustainability

Fair food market for healthy citizens

Public and private food procurement and short food values chains in urban areas

Principal investigators

Referred to

Spoke 01Referred to

Spoke 01